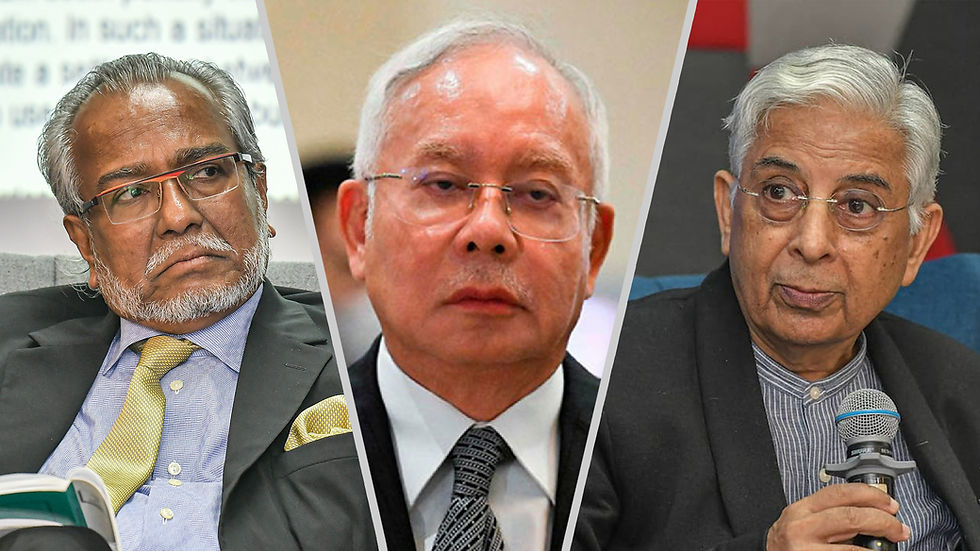

Najib's Pardon: Is It in Line with the Rule of Law?

- Nevyn Vinosh

- Feb 15, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Feb 26, 2024

Before you begin reading this article, there is one important disclaimer:-

In no way is this article intended to challenge the position and/or powers of the YDPA — it is purely an academic discourse on the mechanisms of a royal pardon within the framework of the criminal justice system and its relationship with the rule of law.

There is no contention as to whether Najib’s pardon is legal or provided by law. The power to grant pardons is delineated by the Federal Constitution (Articles 42 and 48), the Criminal Procedure Code and the Prison Regulations — governing the authority of the Yang di-Pertuan Agong (“YDPA”) to grant pardons, reprieves and respites in respect of offences committed.

A Pardons Board (“the Board”), created under Art 42(11) for the Federal Territories, assumes the responsibility of proffering “advice” to the YDPA whereby His Majesty is bound to comply with established procedures of the Board and act on its advice. For a deeper understanding, check out Malaysiakini's comprehensive article on the subject matter.

The scope of this article is to home in on whether the decision to pardon Najib aligns with the core principles of the Rule of Law as well as to address its implications on our legal landscape.

In general, the Rule of Law implies that the formulation of laws, their enforcement, and the relationships among legal rules are themselves legally regulated, so that no one — including the most highly placed official — is above the law.

Should Najib get special treatment?

The Rule of Law advocates for the principle of ‘equality before the law’ or the equal subjection of all classes to the ordinary legal percepts administered by the ordinary law courts. Implicit in this notion is that the government, too, must respect the law. In other words, no one is above the law — the society must be governed by the law and no one stands beyond the ambit of the law. [1]

The Court of Appeal in the SRC case similarly found:

“[398] … The courts in upholding the rule of law would have to do what is necessary to ensure that this modern day plague is eradicated for the good of the nation. The law is indeed ‘no respecter of persons’. All men are equal before the law, and the courts apply the law equally to all."

Why could it be argued that Najib's swift pardon runs contrary to this? Yes, while the pardon is provided by law, but its expedited nature prompts an inquiry into the preservation of remedies of the law. The Rule of Law, encompassing legal constraints on rulers, affirms that the government is equally subject to existing laws as much as its citizens are.

Najib’s conviction was a milestone for the nation to show the world that the no one is above the law — not even a prime minister. Logically one would think that the fact of being an ex-prime minister would be more the reason not to grant a pardon and set an example as opposed to being a catalyst for a pardon.

Contrary to convention, Najib has merely served over a year of his 12-year sentence before being considered for a pardon. This begs the question and speculation as to whether his political and social standing has given his pardon priority or a fast-track.

These are not accusations — but rather reasonable assumptions and questions we, as the Rakyat, find ourselves compelled to pose in the absence of a transparent and clear basis provided by the Board or the Attorney General (“AG”). The question simply boils down to: why is Najib not treated like any of the other 50,000+ prisoners in jail waiting for their pardon? Is it fair to them — who have experienced and lived with the full force of our criminal justice system, having served a substantial portion of their sentences and demonstrated evidence of being reformed before being considered for clemency?

Why should the Pardons Board give their reasons?

Another tenet of the Rule of Law is that the law must be known and predictable to enable individuals to reasonably foresee the consequences of their conduct. It necessitates the law to be sufficiently defined and government discretion sufficiently limited to ensure the law is applied in a non-arbitrary manner. [2]

In Sim Kie Chon, [3] the Supreme Court said that the Board functions only as an advisory body, devoid of decision-making authority, but only offers advice to the King. The Constitution also prescribes an important role for the AG, requiring the Board to consider the AG’s written opinion before tendering its own advice to the YDPA.

So yes, the YDPA and the Board are not obligated to give reasons for their decisions and advice. But surely, it would only be just and constitutionally sound, that the AG — as the guardian of the public interest — to disclose and justify to the Rakyat what his advice entails.

This is especially pertinent given the nature of Najib’s crimes — abuse of position, criminal breaching of trust & money laundering — all of which bear upon elements of public interest.

Providing detailed reasons for Najib’s pardon would be in line with the overarching principle of being governed by the Rule of Law, not men. The inspiration underlying this idea is that to live under the Rule of Law is not to be subject to the unpredictable vagaries of other individuals; it is to be shielded from the familiar human weaknesses of bias, passion, prejudice, error, ignorance or whim — or in short, arbitrariness.

This further highlights the necessity for a Right to Information Act which would promote transparency by mandating all public authorities to disclose information of public interest. It is crucial that such information comes directly from the Board or the AG rather than being released or leaked by unofficial parties. When information is disseminated through unofficial channels, it inevitably raises doubts regarding its credibility and, to a certain extent, contributes to public unrest, as individuals tend to engage in commentary without verifying the authenticity of the allegations.

Although Najib's reduced sentence seems to be all the rave, lest not forget the significant reduction of his fine from RM210 million to RM50 million — this is the money which has been found to be stolen and/or misappropriated from the Rakyat. The lack of transparency regarding the basis for this discount leaves the Rakyat in a state of confusion and frustration.

What precedent does this set?

Najib’s conviction when dealt with in finality by the Federal Court on 23rd August 2023, delivered a resounding warning to all politicians — a stark reminder that even the highest office is accountable to the law. This decision holds a ground-breaking significance because it was the ultimate deterrence that will chart the course for a new political environment.

Najib’s crimes are the worst imaginable case of corruption our nation is ever likely to see — or so I hope. There is legal relevance to this, particularly in the context of sentencing. The maximum sentence for a prescribed offence should be reserved for the worst type of case falling within the prohibition or ‘for the worst cases of the sort’. [4]

Justice Nazlan having considered all relevant considerations found it to be so:

"[2913] I would not hesitate to find that this case can be characterised as one that falls within the range of the worst kind of abuse of position, of CBT and of money laundering because not only of how the crimes were committed, but more importantly also it involved a huge sum of RM42m, had an element of public impact as the RM42m belonged to an MOF Inc company — government funds, and could have originated from the RM4 billion financing from state pension fund (KWAP), and which status of the bulk of RM4 billion is told to be an indeterminate obscurity. And perhaps, most importantly, it involved the person who, at the material time, was in the highest ranking authority in the government.”

This speaks volume on how we as a nation intend to uphold the law and fight corruption. It is counterproductive to the principle of deterrence — one of the central tenets of the criminal justice system. Justice Nazlan opined:

“[2895] No less importantly, at the same time the sentencing court must be mindful of the four key principles and objectives of sentencing — retribution, deterrence, prevention and rehabilitation. Public interest as such should not only reflect the abhorrence of the society against the crime by the imposition of elements of retribution and deterrence in the sentence, but should also ensure the promotion of rehabilitation and reformation on the part of an accused himself.”

"[2898] In my view, the same principles of deterrence and retribution sentencing process in this case, considering the position of the accused and the nature of as well as his involvement in the commission of all the offences of abuse of position, criminal breach of trust and the money laundering charges which in turn are predicated on the abuse of position and CBT offences."

By allowing this, the message conveyed is effectively that there are some who — with enough power, influence, and wealth — stand above the law.

No Remorse, No Mercy

Many cases have described the King’s power as a prerogative of mercy that is unchallengeable in the courts. For most of this country’s history, this practice of executive clemency has functioned as an ancillary feature of the criminal justice system, without attracting much attention or generating much controversy in the vast majority of cases.

Remitting punishment is indeed the moral duty afforded by the Constitution to the YDPA, acting in his official capacity as chief executive. But is Najib deserving of such grace?

Perhaps the most dangerous of all — is to pardon a man who steadfastly believes he’s innocent, one who refuses to accept any wrongdoing and till today advocates for his innocence despite the highest court of our land definitively having found him guilty.

Najib’s conduct not only threatens and undermines our justice system but I dare say it ridicules the Rule of Law — degrading it to merely an academic concept rather than a safeguard of our democracy and constitutionality.

Our Constitution guarantees that everyone is equal before the law — I now wonder if some are more equal than others.

Check out the second part to this article here: Najib's Pardon: Can It Be Challenged?

[1] Ahmad Masum. (2009). The Rule of Law Under the Malaysian Federal Constitution. Malayan Law Journal Articles, 6(c), 1.

[2] Robert Stein. (2019). What Exactly Is the Rule of Law? Houston Law Review, 57, 185.

[3] Superintendent of Pudu Prison & Ors v Sim Kid Chon [1986] 1 MLJ 494.

[4] Bensegger v R [1979] WAR 65 at pg 68.

Comments